The

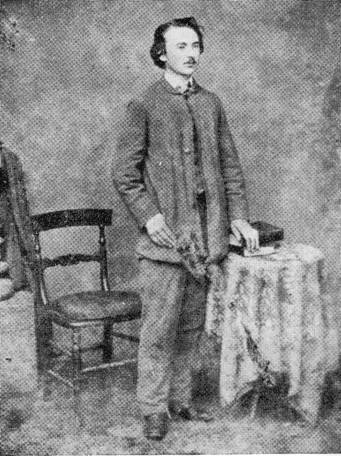

Unknown Boy

This

and the picture below are the only evidence that Thomas Hardy may have fathered

an illegitimate child with Tryphena Sparks.

This

and the picture below are the only evidence that Thomas Hardy may have fathered

an illegitimate child with Tryphena Sparks.

Nellie Bromell showed it

to Lois Deacon in Tryphena’s portrait album and

claimed it was “Hardy’s boy”, variously known as “Randy”, “Randal” or

“Randolph”. Nellie said her half-brother had visited the Gale family a few

times in Topsham. Tryphena’s husband Charles Gale

must have known what had happened before they married. After Tryphena died in 1890, when Nellie was eleven, Hardy and

his brother Henry visited, to place flowers on her tomb. They called in at the

Gales’, and Nellie remembers her Father asking her to attend on the brothers

whilst he made sandwiches for them. He didn’t want to meet Thomas Hardy, by

then a world-famous author.

No written record of any description has been found

of this mysterious boy. Hardy went to great lengths to destroy all records

pertaining to his early life. Even after he died in 1928 his second wife

Florence Emily and literary executor Sidney Cockerell

burnt piles of papers in the grounds of Max Gate, Hardy’s rather gloomy

residence outside Dorchester, on his instructions. The earliest picture of

Thomas Hardy in The Life of Thomas Hardy

by Florence Emily Hardy depicts him as an hirsute

thirty year-old.

He seems to have had no knowledge that Tryphena had kept a portrait album with earlier pictures of

him and her illegitimate son, which obviously she considered of importance. It

came into the possession of her eldest child, Eleanor Tryphena

Gale, later Nellie Bromell.

It has been noted that this boy bears a distinct

resemblance to Hardy’s description of the highly-disturbed Little Father Time

in his last novel Jude the Obscure,

mauled by the critics on its publication in 1895.

On

the left, a photo of Thomas Hardy aged nineteen, taken in 1859. On the right,

Randy, aged about twenty-one, near the time Tryphena

died.

Horace

Moule

Horace

Moseley Moule (pronounced “mole”) is the third member

of the eternal triangle that occurs frequently in Hardy’s novels.

Horace

Moseley Moule (pronounced “mole”) is the third member

of the eternal triangle that occurs frequently in Hardy’s novels.

A member of a large Victorian family of mainly

boys, Moule’s Father was vicar of Fordington

St. George’s church in Dorchester and the family has been identified as the

model for the Clare family in Tess of the

d’Urbervilles.

Horace Moule was a gifted

classical scholar and exercised a considerable influence on the young Thomas

Hardy. He had what were considered at the time to be character flaws, including

alcoholism and a questionable sexuality. Despite his acknowledged erudition he

failed to gain a degree at either Oxford or Cambridge and committed suicide in

1873.

Hardy was estranged from Horace

and Tryphena for two years, from July 1870. He had

committed Tryphena to Horace’s guidance whilst she

was at Stockwell College, Horace being in London and Hardy working as an

architect in Weymouth. Horace reviewed Under

the Greenwood Tree in September 1872 favourably. Hardy incorporated Horace into many of his male characters. Women

are often bedazzled by the Moule character.

The poem Standing by the Mantelpiece, from Winter Words, was published after Hardy’s death. Hardy had visited

Horace at Cambridge in 1872 and watched guttering candles in King’s College

Chapel on another visit seven years later. The speaker in the poem is Horace:

he tells Hardy that, as Tryphena loves him and not

Horace, Hardy must stay alive to watch over her. Horace claims the shroud,

formed by wax as it drips from a burning candle. An alternative romantic

meaning can be drawn from this enigmatic verse:

Standing by the Mantelpiece (Winter Words)

(H.M.M., 1873)

This candle-wax is shaping to a shroud

To-night. (They call it

that, as you may know)—

By touching it the claimant is avowed,

And hence I press it with my finger – so.

To-night. To me twice

night, that should have been

The radiance of the midmost tick of noon,

And close around me wintertime is seen

That might have shone the veriest

day of June!

But since all’s lost, and

nothing really lies

Above but shade, and shadier shade below,

Let me make clear, before one of us dies,

My mind to yours, just now embittered so.

Since you agreed, unurged

and full-advised,

And let warmth grow without discouragement,

Why do you bear you now as if surprised

When what has come was clearly consequent?

Since you have spoken, and finality

Closes around, and my last movements loom,

I say no more: the rest must wait till we

Are face to face again, yonside

the tomb.

And let the candle-wax thus mould a shape

Whose meaning now, if hid before, you know,

And how by touch one present claims its drape,

And that it’s I who press my finger – so.

Florence Emily Hardy writes in The Life of Thomas Hardy: “Speaking generally, there is more

autobiography in a hundred lines of Mr. Hardy’s poetry than in all the novels.”

(p. 392).

As Lois Deacon wrote of Thomas Hardy, in a paper

where she attempts to identify the five women depicted in his poem The Chosen:

“For sixty years he had lived in a multi-caverned hell, into which he had been plunged by a score of

hideous ironies of circumstance. The complex tragedy of ‘concatenated

affections’ between himself, Tryphena Sparks, Horace Moule, Emma Lavinia Gifford and

Charlie Gale had devastated the lives of three of them during the decade

1867–77 and had, perforce, to be hidden during the lifetime of Hardy’s whole

family.”

Thomas Hardy had no children from his two marriages

and none of his three siblings married, so the line is extinct.

To

return to My Lost Prize, click here